The Roots of the Christmas Tree (Another Very Historically Blind Xmas!)

The podcast this holiday season was somewhat overshadowed by a few grim realities, but also by the dark and grisly subject matter that precedes this post. It is pretty difficult to transition from a series on Jack the Ripper to a festive episode. In some way, then, the podcast can be likened to Whitechapel and really all of London in December of 1888, with the awful reality of the horrific murders and the uncertainty over when the killer would strike again still hanging over the city like a pall as many attempted to make merry. There is, though, I think, one interesting connection between the story of Jack the Ripper and the topic of Christmas and its origins, and that is the figure of Charles Dickens. The great Victorian novelist died in 1870, almost 20 years before the Ripper murders, and yet he is inextricably linked to them through his depictions of the East End. In his earlier fiction, he writes about the East End, and even Whitechapel, as a genial and romantic place, the bustling and exciting setting of comedies like The Pickwick Papers. But later in his career, he depicted it as “a jungle of decaying slums housing a starved, feral people,” a squalid and crime-infested district from which, as Madeleine Murphy, author of Dickens and the Ripper Legend states, he suggested “some unknown beast will spring.” Dickens, then, by this view, anticipated the emergence of the Ripper. And he also anticipated the emergence of Christmas, or at least, its most lasting and popular iteration, which hearkens back to Victorian England, when many of the traditions and iconography that persist today began to take definite shape. Dickens is almost synonymous with Christmas. As I write these words, my wife is watching one of the many film adaptations of his classic story, A Christmas Carol, the one starring Patrick Stewart as Ebenezer Scrooge, and within the week, we will be enjoying ourselves at the Dickens Fair here in California, where they attempt to recreate Victorian London, celebrate all things Dickens, and engage in eggnog-fueled holiday revelry for a full month between Thanksgiving and Christmas. There at Dickens Fair the mythology of Dickens is on full display. In some ways, he is responsible for constructing the public conception of Victorian England. Most depictions of Victorian England in fiction and film are perhaps more Dickensian than historical. And he is further credited as the man who invented Christmas. This is no exaggeration. A film by that very name appeared in 2017, based on a book published in 2008, but the notion goes all the way back to an early Dickens scholar, F. G. Kitton, who wrote an article by that name in 1903. What Kitton remarked on, however, was not really the invention of the holiday, or any of its traditions, but rather its resurgence. It is true that the bubonic plague, the collapse of the feudal system, and the Puritan war on Christmas merriment had reduced the holiday to a more sedate and private affair than it had previously been in England, and it is further true that the enormous popularity of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol did much to popularize the holiday again in England, or as fellow novelist William Makepeace Thackeray put it, the novella “was the means of lighting up hundreds of kind fires at Christmas time; caused a wonderful outpouring of Christmas good feeling; of Christmas punch-brewing; an awful slaughter of Christmas turkeys; and roasting and basting of Christmas beef.” There is even a case to be made for Dickens being the person responsible for associating Christmas with snow, since when he wrote about the holiday, he associated it with the bitterly cold winters of his youth, when the River Thames would freeze over, which became a lot less common after the end of the Little Ice Age in the early 19th century. But this too is a dubious credit, since the holiday, even in antiquity, has always been tied to the end of the year and winter solstice, the shortest day, after which come the coldest days. Surely, then, Dickens was not the first to associate the holiday with snow and ice. Perhaps the element most associated with a Victorian and Dickensian Christmas, indeed the tradition and image most associated with the holiday today, second only, it can be argued, to Santa Claus, is the Christmas tree, and this too, it can be said, was popularized by Dickens, who wrote an essay about them in 1850, describing the Christmas tree as a “pretty German toy,” a very new tradition that was then catching on in the English speaking world, and which Dickens used as a metaphor to wax nostalgic about childhood and the lessons of life. Here we find Dickens again at the forefront of a Christmas tradition for which he can’t really be given credit. He was not the first nor even the most effective champion of this tradition, and just exactly how new it really was in the mid-19th century, and where it came from, remains one of the most complicated and debated topics related to Christmas. So join me now, around our tree, so brightly festooned with glittering ornaments and lit tapers, as I welcome you to yet another Very Historically Blind Christmas, this one all about the Christmas tree and its roots.

*

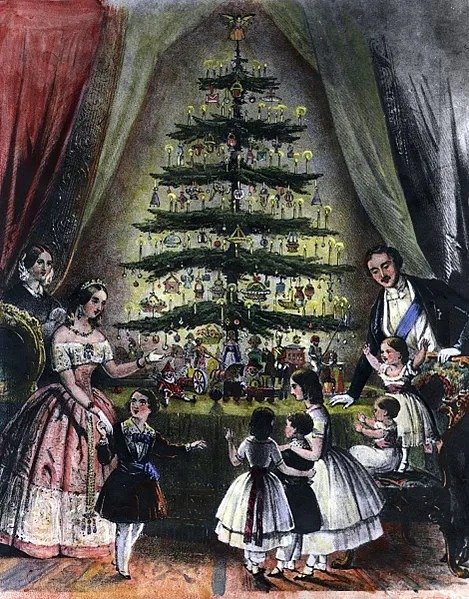

I have spoken on the topic of Christmas trees and their origin before. In my very first holiday special, all the way back in 2018, talked about it in a couple of paragraphs, and it came up again last year, in my patron exclusive about the bizarre mushroom theory of Christmas, but it is a topic that proves far more complex and full of uncertainty and mystery than I managed to show in those brief mentions. As I said back then, there are a great many notions, perpetuated by social media meming, that the Christmas tree is some sort of very ancient pagan practice, and that Christians are somewhat foolish in thinking it’s not a pagan survival that they co-opted. One bible verse typically thrown in their faces is Jeremiah, Chapter 10, verse 3 and 4, “For the customs of the peoples are false: a tree from the forest is cut down..they deck it with silver and gold….” What is typically omitted or glossed over is the part that says the felled tree is “worked with an ax by the hands of an artisan,” and that in the context of the actual verse, it is talking about the carving of wooden idols plated in silver and gold and fastened to a wall with nails, not a tree hung with ornaments. It is a blatant misconstruing of the scripture to attack Christians, and that’s just bad form. Really, we don’t need to rely on falsehoods to reveal the hypocrisies of many Christians. In truth, the Christmas tree, as we today recognize it, did not really appear until the 19th century, and in a narrow way, the Dickens movie, The Man Who Invented Christmas, gets it right. In it, the actor Dan Stevens, who plays Dickens, has a decorated tree in his parlor and remarks that “The Germans call it a Tannenbaum. It's a tree for Christmas. A Christmas tree, I suppose. Now the royal family have got one, it'll be all the rage.” Now, it’s wrong to suggest that a tannenbaum is a Christmas tree, or that the song O Tannenbaum can be accurately translated as O Christmas tree, as is common in English. In truth, a tannenbaum is just a fir tree, and the subject of the 18th century song was a living evergreen, persisting through the bitter cold and remaining alive. To associate it with a tree that we cut down for decorative purposes rather misses the point, but that is exactly what happened in the 19th century, when the song was first rewritten to take on a more festive seasonal symbolism and then was translated into English as referring explicitly to a Christmas tree. The film is right, however, in ascribing a German origin to modern day Christmas trees, and in crediting the British royal family for popularizing them. The film is referring to Queen Victoria, or more specifically to her German consort, Prince Albert, who in 1840 imported some spruce trees from Bavaria to uphold his German Christmas tradition in England. It is not entirely accurate that the tradition would have spread to the Dickens home by 1843, the year he published A Christmas Carol, as the film depicts, however, because it did not really take off as a popular tradition until some years later, when the press publicized it as a yearly tradition in the royal household. In 1848, the Times and the Illustrated London News both published stories describing the royal christmas tree, along with engravings illustrating it, and by the following year, the tradition had taken hold, and the same newspapers were printing stories with recommendations on how Londoners might decorate their own trees. Hence the 1850 essay in which Dickens effused about the newfangled German Christmas tree. But as new as it may have seemed to the English public in 1848, there was, indeed, as many have claimed, a longer history to this practice.

An pretty edition of the Dickens essay on the Christmas Tree.

Even within England, the practice was not unknown. Queen Victoria herself reminisced about a Christmas season from her youth, in 1833, during which she remembered “trees hung with lights and sugar ornaments.” It may be, then, that the decoration of a tree at Christmas was only a tradition at court before Victoria and Albert popularized it, for as is frequently pointed out, there is record of an earlier British royal putting up a tree. In 1800, George III’s wife Queen Charlotte apparently put up and decorated a yew tree with wax candles and clusters of fruits and nuts to delight the children attending a holiday party in the Queen’s lodgings. This appears to have been the beginning of the trend among the upper classes in England. The fact that in previous years, Charlotte had only put up and decorated a single bough of a yew tree, as was common practice in the German duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, where Charlotte was from, has led some to speculate that she was the Christmas tree “inventor,” that she was the first to innovate the decoration of a whole tree rather than just a branch. Supporting this is a description of the tradition in Mecklenburg-Strelitz as observed by the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1799: “On the evening before Christmas Day, one of the parlours is lighted up by the children, into which the parents must not go; a great yew bough is fastened on the table at a little distance from the wall, a multitude of little tapers are fixed in the bough ... and coloured paper etc. hangs and flutters from the twigs. Under this bough the children lay out the presents….” However, while in this particular duchy the tradition was the decoration of a single bough, it is clear that elsewhere in Germany, the tradition was to bring in and decorate a whole tree, in some places a yew, in others a box tree, and elsewhere a fir tree. The first mentions of these German trees extends much further back, especially around Strasbourg, on the Rhine in the Alsace region in what is eastern France today. In the middle of the 17th century, theologian Johann Konrad Dannhauer wrote about “the Christmas- or fir-tree, which people set up in their houses [and] hang with dolls and sweets,” and like many a historian and theologian since, he too was baffled by the origin of the tradition, saying, “Whence comes the custom, I know not.” By his time, it had firmly taken root, it seems, but at the very beginning of that century, in 1605, an anonymous writer had described the same tradition in the same place, “They set up fir trees in the parlours at Strasburg and hang thereon roses cut out of many-coloured paper, apples, wafers, gold-foil, sweets, etc.” And it appears that the practice of cutting down trees for Christmas was widespread even midway through the previous century, as in Upper Alsace, in 1561, a limit on the number and size of pines that people were allowed to cut down was imposed.

According to one legend, the tradition originated some 500 kilometers from Strasbourg, in Wittenberg, on the other side of Germany. It is claimed that the German church reformer Martin Luther took a winter stroll one night and admired the stars shining through the evergreen canopy of the trees overhead. According to this tale, Luther cut down a tree and brought it home, hung lit candles in its branches to simulate what he had seen, and turned it into a sermon for his family about the Christmas star. This story just sounds totally false, and sure enough, it is entirely unsupported by any historical documentation. There is a far better case to be made that Martin Luther originated the Christkind or Christkindle traditions of a Christmas giftbringer who could be likened to the Christ child, wanting to take emphasis away from the Catholic Saint Nicholas, but this claim about the Christmas tree seems bogus. It does appear to be the case, however, that Christmas trees were largely a Protestant tradition when the custom did take root. In fact, they came to be called Lutherbaum, or Luther trees, and by the 19th century, Catholics derisively referred to Protestantism as the “Tannenbaum religion.” However, the first confirmed Christmas tree in Wittenberg, where Luther supposedly invented them, would not appear until a couple hundred years after Luther’s death in 1546. And since, about a hundred years after Luther died, the aforementioned Lutheran theologian Johann Dannhauer still had no idea where the custom had originated, it seems very unlikely that Martin Luther invented it. In fact, all signs point to Strasbourg, in the Franco-German Alsace, as the birthplace of Christmas trees. Strasbourg today boasts that it is the capitale de Noël, the Capital of Christmas, as its Christmas market was held as far back as 1570, and its annual raising and decoration of a Christmas tree in the Strasbourg Cathedral is said to have taken place as far back as 1539. Going further back, into the 15th century, the Strasbourgian town clerk Sebastian Brant attempted to forbid the cutting down of trees around the end of 1494, so widespread was the practice of bringing felled trees into the home. And in 1419, a record from a Fraternity of Baker’s Apprentices in Freiburg, just south of Strasbourg, mentions a tree inside the Hospital of the Holy Spirit that was decorated with gingerbread, wafers, tinsel, and apples. This is what we find when searching for the invention of the Christmas tree—each time we think we find its “inventor,” Queen Charlotte, Martin Luther, when we look further back we find still the Christmas tree standing and shining, the beacon of a festive winter holiday.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert popularizing the Christmas tree.

Now we’ve traced the Christmas tree back to the tail end of the Middle Ages, to Alsace in the Rhineland, then a part of the Holy Roman Empire, and the earliest of descriptions we can find, in Freiburg, has them decorated with bright red ornaments, such as apples, and other edible ornaments, including wafers. One idea for the medieval origin of the Christmas tree has to do with various legends surrounding trees and plants miraculously blossoming around Christmastime. According to one 1430 account, an apple tree in Nuremberg “bore apple blossoms the size of a thumb on the night of Christ’s birth,” causing citizens to keep vigil around it. This lone incident could not have been the origin of Christmas trees, since we have already seen the tradition in earlier reports, but this one corresponds generally to many traditions about miraculous blooming in midwinter, most of them having to do with plants that, strangely, bloomed or bore fruit in this unusual season, most of which are now largely associated with Christmas, like holly, mistletoe, the poinsettia, also called the Christmas Star, and the hellebore, or Christmas Rose. Indeed, there is a story out of the Middle Ages of the miraculous blooming of actual red roses associated with Christmas. It is said that St. Francis of Assisi discovered a rosebush miraculously in bloom in the snow at Christmastime. There are different versions of this legend, which helps to demonstrate its mythological character. In one, Francis is leaving a convent in San Damiano and tells the sorrowful nuns there that they will see him when the roses bloom again, whereupon they see the miracle of the winter roses. Another version has it that he laid down on the thorns of a barren rosebush one night in order to feel the pain that Christ felt, and in the following days the roses bloomed. The simple fact, though, is that a miracle having to do with roses was quite common in hagiography. Often it was the transformation of other things into roses, but in the case of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary and Our Lady of Guadalupe, the appearance of fresh roses in winter became an established motif. While there is little evidence to support that these legends evolved into a tradition of cutting down evergreen trees and adorning with red ornaments to represent a miraculous blooming, there is some clear sign that these miraculous blooming traditions contributed to other Christmas customs, such as bringing cuttings from certain trees, including hazel, linden, cherry, plum, and apple trees, into the warmth of the home and placing them in water so they would bloom unseasonably around Christmas. These not being evergreens, though, it would seem an entirely separate tradition from Christmas greenery and Christmas trees, with perhaps the crossover being the common Christmas tree decoration of paper flowers that we later see.

While these miracle blooms of apple blossoms gets us closer to the trees hung with apples, it is another theory on the origin of the Christmas tree tradition that takes us all the way there, one which I and most scholars find the most convincing. In the Middle Ages, in Germany and elsewhere in the Holy Roman Empire of Central and Western Europe, there was a predecessor to the nativity play we usually associate with Christmas time. These were called Paradise Plays, or Genesis Plays, and they reenacted the events of Adam and Eve’s original sin and banishment from Eden. During the height of the scribal system, when many could not read and books were a luxury possession of the church, read and copied by monks, and of royals tutored in Latin, such mystery plays were a common vehicle by which to teach the public about major scriptural narratives and doctrinal points. These plays in particular, depicting the Biblical Creation myth, Satan’s temptation of Eve, and the Fall of Man, may seem like an odd play to stage on Christmas Eve, but it must be remembered that December 24th was the Feast of Adam and Eve. In focusing on the story of original sin just before Christmas Day, Christians of the Middle Ages were reminded of why Christ was born, about the need for redemption that he fulfilled. So though it may seem an entirely unrelated story, it was not viewed as such. This much can be clearly discerned in medieval art, in which the Christ child is commonly seen accepting an apple from Mary. As you might imagine, these Paradise Plays had reason to depict an apple laden tree in the garden, the fruit of which Adam and Eve were forbidden to eat. The problem was, apple trees were bare, their fruit having been harvested already. Nor would it have been practical to cut down a healthy, fruit-bearing tree to serve as a prop. This being wintertime, it was therefore common to cut down a fir tree for these productions and adorn them with apples. According to the current best guess of scholars, Germans kept this tradition past the Middle Ages, bringing these Paradise trees into their homes, adorning them not just with apples, but with eucharist wafers to further represent Christ’s atonement for Original Sin. Parallel to this tradition was one that arose out of the Ore Mountains in Western Germany of having a so-called Christmas pyramid, or wooden carousel of shelves lit with candles and decorated with Christian scenes, like the Nativity. Originally, this was called a Lichtergestelle or “light-stand,” and was meant to brighten spirits during dark and cold months. It was adorned with evergreen cuttings to further raise spirits. As near as most scholars can discern, then, somewhere in the murky Middle Ages, in the homes of common Germanic folk in the Holy Roman Empire, the custom of raising a Paradise tree and of making a Christmas pyramid merged, and the Christmas tree was born, lit with candles to ward off the dark, decorated gaily with bright and colorful baubles—something like apples or miraculous winter blooms—and with edible treats to raise spirits—something more tasty than the eucharist wafers of old—and eventually the origin of the tradition was forgotten.

A depiction of Martin Luther celebrating with a Christmas tree.

Or at least, this is current scholarly consensus, lacking definitive evidence of the custom’s step by step evolution but making perfect sense chronologically, geographically, and culturally. So that’s the end of it, right? Not quite. Many are the claims that the origin of the Christmas tree stretches much further back, deriving from ancient pagan customs, and therefore serving as an example of pagan survival within Christianity. I am open to such theories, as I have indicated in previous episodes on Christmas, but I am also very critical of them when they lack evidence and logic, as was the case, for example, in the mushroom theory of Christmas, which attributes everything Christmasy to the practices of Siberian shamans and their use of psychotropic mushrooms. So let’s look at these theories. The most widespread is that the Christmas tree is some sort of Scandinavian tradition derived from pagan Norse belief. At first blush, there is some weight to this in that Scandinavian peoples are Germanic, and there was cultural and ethnic migration, such that traditions could have been transplanted from Northern Europe to Central and Western Europe. Relatively early evidence of Christmas trees does extend northward from Germany, as well. In Latvia, for example, a merchant guild’s records indicate the appearance of a Christmas tree as early as 1510. This is indeed early, but not as early as other records I’ve discussed, making their claim that it was the first Christmas tree relatively easy to refute. North of there and 70 years earlier, other records suggested a decorated Christmas tree was put up for a dance. Some of these records are questionable, however, as the brief descriptions don’t indicate whether it was an evergreen tree with foliage or more of a stripped tree decorated as in maypole traditions. Looking at the actual pagan beliefs of the Norse, it is clear that, after their conversion to Christianity, their festive winter solstice traditions, yule, have made a big impact on Christmas traditions, and several of them are indeed comparable to the Christmas tree custom. First, decoration with greenery was central to yuletide celebration, and several of the specific plants sacred to the Norse have since become deeply associated with Christmas, including holly, ivy, and mistletoe. Indeed, one of the central ceremonies of yuletide related to the cutting down of a tree and bringing it into the home. But it wasn’t an evergreen, and they didn’t put it up and decorate it. It was likely a birch or oak, and they stripped it, treated its wood, and burned it slowly over the twelve days of yuletide. More than that, the Yule log custom did not noticeably change to become some other tradition, for it remained a tradition of warming the home with a single slow-burning log, although elsewhere in Europe it came to be called a Christ log or Christmas log.

A depiction of the Tree of Life that indicates its similarity to Christmas trees.

Perhaps the most tempting connection to make between yule and the Christmas tree is the idea of sacred or holy trees and that the Norse worshipped them. The most prominent tree in their belief system is the World Tree, Yggdrasil, the meeting place of the gods, its roots and canopy uniting the heavens and the Earth. But why is Yggdrasil correlated with Christmas trees according to this theory? It’s never depicted as a fir tree, but more as an ash, and it’s not decorated. It cannot just be because they are both trees. By that logic, any mythological tree could be claimed to be the inspiration of the Christmas tree. Is it logical to claim that the sacred cypress that was said to have grown from a branch Zoroaster carried back from Paradise was the inspiration for the Christmas tree? Or that the Christmas tree was meant to represent the oracular Oak of Dodona from Greek myth? No, and the claim of Yggdrasil being its inspiration is equally untenable. But the myth of Yggdrasil may have spawned the common worship of numerous real trees by other Germanic pagans, such as the Irminsul, sacred to the Saxons, the tree at Uppsala in Sweden, and Donar’s Oak, also called Thor’s Oak and the Oak of Jove, worshipped by the pagan predecessors of the Hessians. All of these were destroyed by Christian missionaries, making it an odd claim that they would have incorporated tree worship into their own religion when they went to great lengths to stamp out the practice. But one account, that of Donar’s Oak, as told by proponents of the pagan survival view of Christmas trees, claims that St. Boniface cut down the pagan oak tree and in its place a young fir tree miraculously sprouted, converting all the pagans to Christianity. The implication, of course, is that Christmas trees originated as a remembrance of this miracle. First of all, all of these claims really rely on the notion that Christmas trees are worshipped, which an uptight iconoclast might make but which I find unconvincing. Second, even if this miracle story were true, which it obviously isn’t, being just another exaggerated tale about a saint told by a hagiographer, it doesn’t really explain why this symbol would afterward be cut down, brought home, and decorated. And third, if we actually check the source, the hagiographical Life of St. Boniface, written by an 8th century bishop named Willibald, it is not even true. According to the source, when Boniface notched the tree, struggling to actually fell such a massive tree, it suddenly “burst into four parts” and fell. There is no mention of a young fir tree sprouting in its place. It afterward says “four trunks of huge size, equal in length, were seen,” but whether this refers to new trees is not clear, as it seems to only be describing the four parts into which the original oak had burst. Regardless, after the incident, they didn’t start worshipping what was left; they used the wood, it says, to build a new structure, an oratory dedicated to St. Peter from which Christianity could be preached. So we find that the only feasible evidence for the idea that pagan Germanic tree worship transformed into a Christmas tree tradition is a completely embellished and revised version of an already dubious hagiography, a genre of literature known for its fantastical invention and lack of reliability as historical source material.

If the idea that Christmas trees originated in yule traditions is unsupported and lacking any strong evidence, this does not bode well for all the other theories of Christmas trees as pagan survivals, which are even weaker. Some claim it can be traced to Egypt in 3000 BCE, when palm branches were brought into the home to honor Isis, mother of Horus, who like Christ was said to have been born on the solstice. Yet no thought is given to how the tradition might have migrated to Europe or why it reappeared without precedent there thousands of years later. Also I saw claims that Druids decorated oak trees with golden apples and candles to honor Odin, but Druids did not worship Scandinavian deities. Some have attempted to draw comparisons between their pantheons, but to say they honored Odin or Woden as I saw repeated time and again is just patently false. Also, I saw no evidence for the claims about the decoration of trees by druids. It certainly wasn’t mentioned in the earliest writings about Druids by Julius Caesar. In Pliny the Elder, their religious ceremony surrounding an oak is described, which involved the veneration of mistletoe, which is at least a bit Christmasy, but nothing about golden apples and candles. So until I can find real support for this, and please send it if you have it, I have to consider it a frequently repeated myth. Myths like this about the pagan origin of Christian traditions get made up one time by unscrupulous writers and then live on, repeated in perpetuity as if they are fact. This is the case with many misconceptions about the origin of Easter iconography and traditions, which originated in the poorly researched purposely misinformative book The Two Babylons by Alexander Hislop, written as an attack on Catholicism, which I spoke about in an old episode. Well, as it turns out, Hislop contributed to the Christmas tree confusion as well. Based on an illustration of a coin depicting a snake wrapped around what looks like a tree stump, Hislop spins a fanciful story about King Nimrod’s wife deifying her dead husband. According to him, she said a young tree grew in place of a dead stump, symbolizing her husband’s rebirth, and that Nimrod came back to life every year on his birthday, which happened to be December 25th, and would leave gifts beneath that tree. This, it was claimed, was the origin of both the Yule log and the Christmas tree. No citations or sources are cited for this claim. Only the image of the coin with a snake around a stump, or maybe it is a ruined pillar? The coin also pictures a palm tree and a sea shell and reads “Tyriorum,” indicating some connection to Tyre, but no provenance or context whatsoever is provided. The illustration is labeled only “The Yule Log,” and a source is given: “MAURICE'S Indian Antiquities, vol. vi. p. 368.” This is Thomas Maurice’s Indian Antiquities, or Dissertations on Hindostan, published 1812, and the coin does not appear in it. It is quite apparent that Hislop, as he did in so many other claims, was just making stuff up. Yet in the 1980s, a pioneer of televangelism, Herbert Armstrong, founder of the Worldwide Church of God, promoted this misinformation in a booklet called “The Plain Truth about Christmas,” and now you can find it parroted on social media, along with a lot of other nonsense made up by Hislop, such as that Easter is really about the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar, and you see it popping up on every major liturgical holiday. The reality of the survival of pagan traditions in modern Christianity is far more nuanced. Are there elements of paganism in the Christmas tree tradition? Insofar as the traditions of decorating one’s home with greenery is a custom with long pre-Christian roots, sure, but at a certain point, it’s impossible to differentiate what was pagan custom and what was simply a human habit. Some promoters of pagan survivalism in Christmas tradition will claim that singing is a pagan custom, and feasting, and bells, and lighting candles and fires, when in reality, people just sing and feast when celebrating, and since the invention of bells, it is common to ring them. Winter solstice is the longest night of the year, after all, marking the start of the coldest season. Can we really call the lighting of candles and the kindling of fires in the hearth a pagan tradition, when it is also just a way to stave off the dark and the cold? There is mystery and cultural heritage behind the Christmas tree tradition, but that doesn’t mean that we can trace it back through endless iterations to the furthest antiquity.

A depiction of St. Boniface chopping down Donar’s Oak.

Further Reading

Barnes, Alison. “The First Christmas Tree.” History Today, vol. 56, no. 12, Nov. 2006, https://www.historytoday.com/archive/history-matters/first-christmas-tree.

Barth, Edna. Holly, Reindeer, and Colored Lights: the Story of Christmas Symbols. Seabury Press, 1971.

Brunner, Bernd, and Benjamin A. Smith. Inventing the Christmas Tree. Yale University Press, 2012. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vkr9c.

Tille, Alexander. Yule and Christmas: Their Place in the Germanic Year. David Nutt, 1899.